Grief is the thing with feathers

Max Porter

April 13, 2020

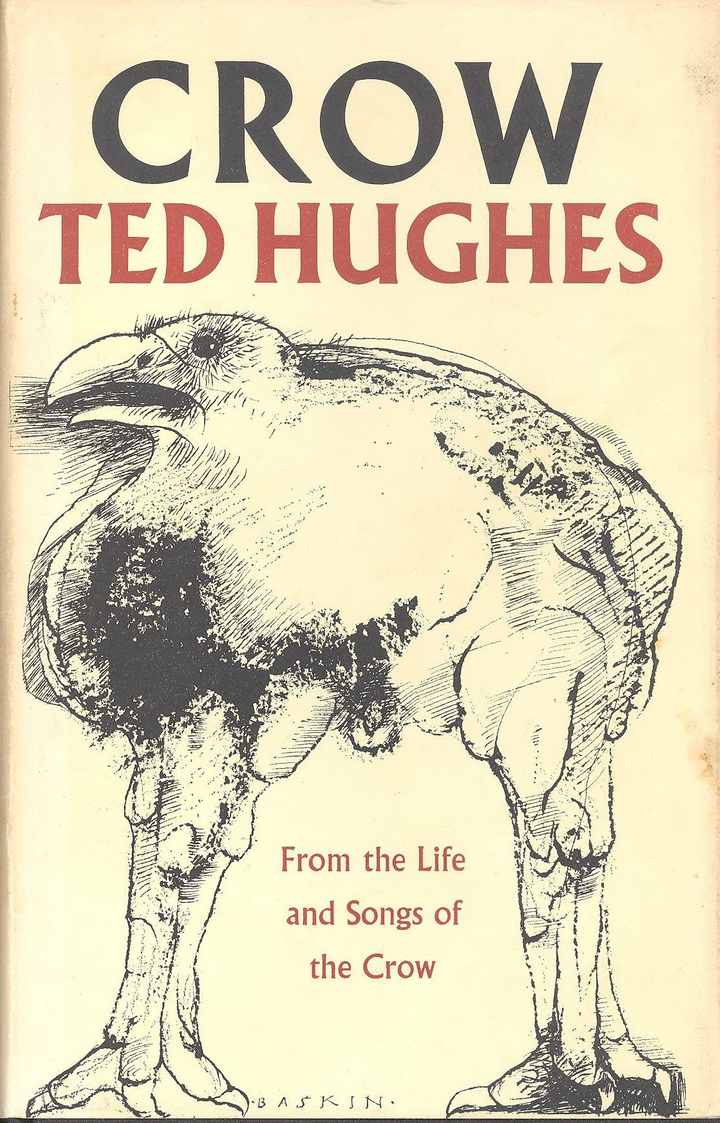

Max Porter’s first novel - Grief is the thing with feathers, finds a writer with two young sons suddenly widowed. There is no interrogation of mortality in this short book, nor any deliberation of why or how she passed away. Rather, this short story focuses on those left behind. The book is shaped around the arrival of a central character - Crow, who appears (whooping and spluttering) to pave a roadmap of life without mum. Straight out of the pages of Ted Hughes’ seminal works, this oversized corvid plays many roles in its more-than-metaphorical personification of grief.

Porter unabashedly splices forms together, skilfully juxtaposing prose, poetry, memoir, children’s tale and lyrical onomatopoeia lint, flack, gack-pack-nack. Each character has their own medium, which has been carefully crafted to reflect the way in which each is living with and despite of their grief. The sum of its parts, Porter’s first book reads like a knotted string of recollections that are tangible, deeply resonant, grounded and earthly; pinned against an unavoidable non-presence of no mum, no mum, no mum. As a whole, this little book is an astounding window into mourning. It encapsulates humanness in its ever changing breadth, moment to moment, across a decades. It is at once painful, playful and funny, incredibly grounded and simultaneously other-worldly. It should be treasured.

Key to the exposition is the nature of mum’s death. Being sudden and unexpected, both the boys and dad reflect upon the finality of a death without any chaos or drama or a slow unfurling of biological decay. They describe the way it allowed grief to both stampede through the front door and simultaneously tiptoe in through the back - sinking into the furniture and half empty fridge: “every surface dead mum, every crayon, tractor, coat, welly, covered in a film of grief.”

Ill people, in their last day on Earth, do not leave notes stuck to bottles of red wine saying ‘OH NO YOU DON’T COCK-CHEEK’. She was not busy dying, and there is no detritus of care, she was simply busy living, and then she was gone.

The boys chapters read more like snippets of solid events as remembered by children, descriptive and whimsical. In the beginning, their segments are short and full of small moments of understanding that their life has irrevocably changed. They dream up fairytales where they are are princes, they fantasize about running far away and becoming big strong men who don’t need a mother. They dream of trees, and sword fights, and adventure. Tender moments of humour and childish thoughts ease the blackness.

Dad are you dead?

Dad are you dead?

A long whining fart answered and Dad kicked out.

Course he’s not dead, you boob, said my brother.

The chronology of the novel is guided by the evolution of grief. It being a short read, by the time you’re half way through it can easily skip a decade without affecting the flow. Time slides by in milestones and small impressionable moments where she is most missed. “We were careful to age her, never to trap her. Careful to call her Granny, when Dad became Grandpa. We hope she likes us.”

Alongside the abrupt changes in form, Porter’s writing style, tone and flow adapts to each character seamlessly. We learn that Dad is a writer very much enthralled by Ted Hughes, and is in the beginning stages of completing a manuscript analysing Hughes’s anthology Crow.

His sections are eloquently written, with both short simple prose in sections that seem most bleak, and verses more akin to a Steinbeck passage - sometimes sardonic, other times more objective. In one of the opening Dad sections, Porter writes - “Of course, I was becoming expert in the behaviour of orbiting grievers. Being at the epicentre grants a curiously anthropological awareness of everybody else; the overwhelmeds, the affectedly lacksidaisicls, the nothing so fars, the overstayers, the new best friends of hers, of mine, of the boys.” If you have ever known someone whose lost someone, it’s likely you recognise these categories.

Porter’s ability to portray an adult’s comprehension of raw loss, however, is often most poignant in the spaces where the sentences are shortest.

She won’t ever use (make-up, tumeric, hairbrush, thesaurus).

She will never finish (Patricia Highsmith novel, peanut butter, lip balm).

And I will never shop for green Virago Classics for her birthday.

I will stop finding her hairs.

I will stop hearing her breathing.

In the unique depiction of grief as a corvid, Porter also draws upon trickster mythology, a homage to a main source of inspiration for Hughes’ Crow. In what becomes a characteristic breaking of the fourth wall, Dad explains how his manuscript would dissolve “the boundaries of form because Crow is a trickster, he is ancient and post-modern, illustrator, editor, vandal…”. This of course, stands true also for Porter in this novel. In many cultures, crows are emblematic of death. In another reflexive moment, Crow explains “I was, after all, ‘the central bird… at every extreme’. I’m a template. I know that, he knows that. A myth to be slipped in. Slip up into.” In this household however, shape-shifting and betraying tangible boundaries in an effort to be all things, Crow is most of all a friend. He goes into Dad’s office and curls up on chair, offers opinions about literature and history books. He does not comment on loss, he does not need to. His presence, sometimes great sometimes light, is enough of a reminder.

Perfect devices: doctors, ghosts and crows. We can bring things other characters can’t, like eat sorrow, un-birth secrets and have theatrical battles with language and God. I was friend, spectre, crutch, toy, phantom, gag, analyst and baby sitter […] A smack of black plumage and a stench of death. Ta-daa! This is the rotten core, the Grunewald, the nails in the hands, the needle in the arm, the trauma, the bomb, the thing after which we cannot ever write poems, the slammed door, the in-principio-erat-verbum. Very What-the-fuck. Very blood-sport. Very university historical.

The death of the boys grandmother early on comes as a sweet and gentle reminder that life goes on, and thus - so must death. It is homely and safe and expected. Gran’s last words to the boys - being allocated belongings and recieving advice, is wholesome and natural, and there are no crows in sight. Corvids, it seems, arrive only where acceptance seems far away, and hopelessness lingers.

The masterful way this short novel traverses big concepts in so few words is a real testament to Porter’s power as a writer. Big themes including fatherhood, fragility, time, change, faith and loss are all delicately interwoven in subtle threads throughout. In the end, time passing - the ebbs and flows of missing her - do not need logging in careful anticipation of an end date. In a perfect encapsulation of Porter’s ability to move a reader through the blackness with effortlessly relatable comedy, are Dad’s thoughts on the future.

Moving on, as a concept, was mooted, a year or two after, by friendly men on behalf of their well intentioned wives. Women who loved us. Women who knew me as a child.

Oh, I said, we move. WE FUCKING HURTLE THROUGH SPACE LIKE THREE MAGNIFICENT BRAKE-FAILED BANGERS, thank you, Geoffrey, and send my love to Jean.

Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project. I refuse to rush. The pain that is thrust upon us let no man slow or speed or fix.

Read it, share it, treasure it.